‘An Unfinished Masterpiece’, Philip Burne-Jones c. 1900

Among the Bohemians

Experiments in Living 1900-1939

Among the Bohemians charts the valiant experiments of the artists, poets, writers and composers, who in the early twentieth century declared war on Victorian conformity. Rebels and free spirits, these were the pioneers of a domestic revolution. Escaping the confines of the society into which they had been born, they carried idealism and creativity into every aspect of daily life. Deaf to disapproval, they got drunk and into debt, took drugs, experimented with homosexuality and open marriages, and brought up their children out of wedlock. In the spirit of liberty, they sacrificed comfortable homes and took to the road in gypsy caravans or moved into spartan garrets in Chelsea.

Yet their choice of a free life led all too often to poverty, hunger, addiction and even death. Among the large cast of flamboyant characters depicted in Among the Bohemians are such giants of the artistic scene as Augustus John, Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill, alongside their literary counterparts Dylan Thomas, Robert Graves and Arthur Ransome. Lesser-known (but no less colourful) characters include Kathleen Hale, Iris Tree, Philip O'Connor, Nina Hamnett and Ruthven Todd.

The book holds a magnifying glass over the habits and domestic lives of artists and writers in this country for the forty-odd years before the Second World War, revealing tendencies, overlaps and above all aspirations in common among an entire sub-section of society, that set them apart from the vast mass of conventional British people. Among the Bohemians uncovers the story of a tiny, avant-garde minority who possessed a special cohesiveness beyond movements and styles in art, and whose daily lives seemed touched with an artistic consciousness that bore vivid witness to an ideal about how one should live.

The Bohemians accelerated the process that was to change the social scene in Britain for ever; they opened the doors for that other great moment of change – the 1960s. Today we still owe many of our freedoms to that pioneer generation.

I am available to promote Among the Bohemians through appearances, interviews and articles.

For further information contact Amelia Fairney at Penguin amelia.fairney@uk.penguingroup.com

Excerpts from Among the Bohemians:

Excerpt 1

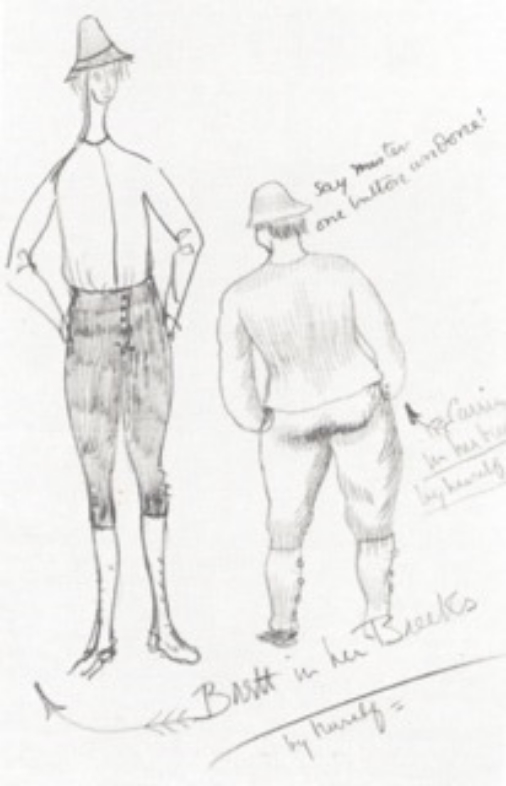

from Chapter 5 “Glorious Apparel”

This was the great era of disguise and fancy-dress; it was as if the combined corps de ballet of La Boutique Fantasque, Carmen and Schéhérazade had all joined hands and taken to the streets, dancing into every salon, dance-hall and night-club, and making their final entrance en masse at the Royal Albert Hall. For this was the usual venue of the Chelsea Arts Ball, an unmissable event in the Bohemian calendar, and the moment when artistic and high society London united to let its collective hair down - its great innovation being that fancy dress was compulsory.

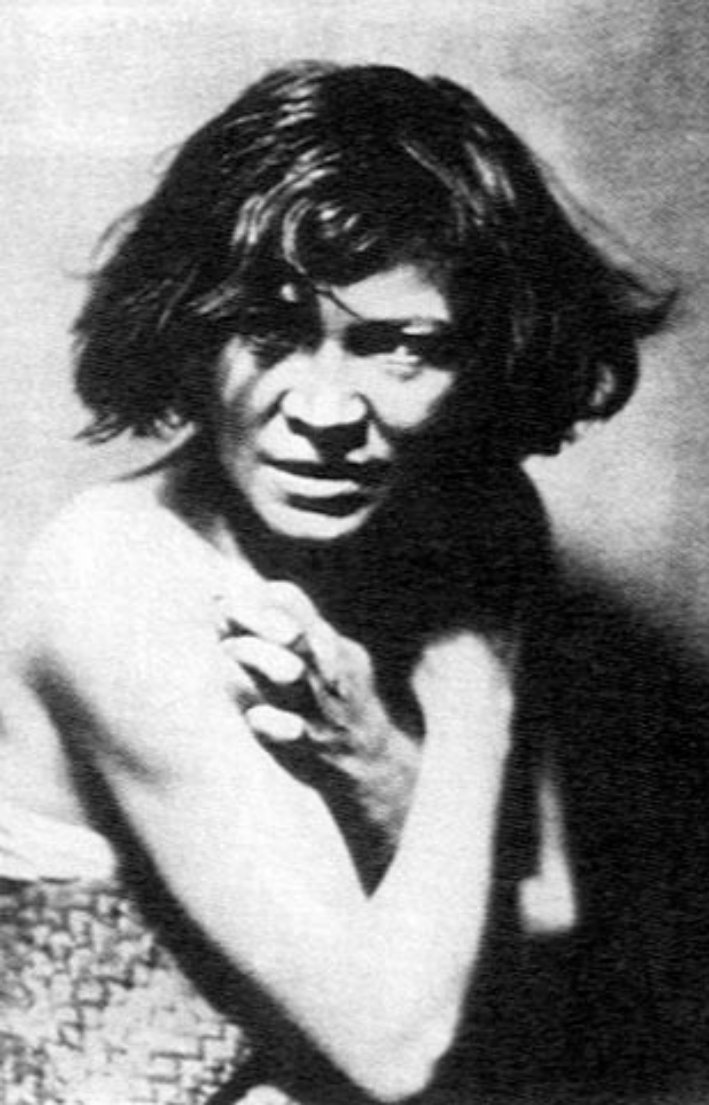

Dorelia by the Gate, Augustus John, 1910

On Mardi Gras 1910 four thousand three hundred revellers arrived at the Albert Hall for the biggest motley extravaganza ever held in London, a whirling, dancing crush of crazy outfits. Most of the artists had designed their own costumes. Forty girl art students transformed themselves into an eighty-legged microbe - the “Flu Germ”. Flashing its electrically-lit red eyes, it wove its way past a cute little model en travesti astride an attenuated giraffe, while to the music of massed bands, Halley’s Comet whirled across the floor with Joan of Arc, and an elephant turkey-trotted with a Sioux chieftain. Meanwhile Romeo and Juliet shared a joke with a pair of cowboys, and teddy bears, red devils, mad hatters and toreadors danced till dawn. ‘The fun of it all!’ sighed one delirious party-goer, remembering that phantasmagoric night.

Never perhaps has so much mileage been extracted from the dressing-up box as during those flamboyant early decades of the twentieth century. 1910 saw possibly the most outrageous example of exotic stunt-dressing, if one can call it that, when His Imperial Majesty the Emperor of Abyssinia and his suite arrived to inspect the flagship Dreadnought at anchor in Weymouth harbour. None of the officers on board suspected their real identities: Duncan Grant, Anthony Buxton, Guy Ridley, Virginia Stephen and her brother Adrian Stephen. Despite a few close misses - as when the rain threatened to wash away Duncan’s moustache - the impersonators remained undiscovered. The episode would slip into history, and mythology – a milestone among masquerades.

The Dreadnought Hoax, 1910. Virginia Woolf (Stephen) is far left

Perhaps the Dreadnought Hoax figured in Virginia Woolf’s memory of that year when she later wrote, ‘on or about December 1910 human character changed’. Writers and artists were making pre-War London feel like the most exciting place on earth to be alive. But modernist camp-followers needed to feel that their external guise was of a piece with their experimental art, and that it expressed their ideal of authenticity as opposed to the fake, gutless complacency of the bourgeoisie. They were determined to stand apart from the herd, to cast a new sense of identity. What was wrong with tennis pumps under evening dress, with breaking the rules in a black wedding dress, or walking down the Tottenham Court Road in odd shoes and coloured stockings - if they showed you were original?

Excerpt 2

from Chapter 6 “Feast and Famine”

Kitchen Still Life, Duncan Grant, c. 1960

Convenient, cheap and nourishing, the rôle of eggs in the lives of artists may well have been unrecognised. How many masterpieces owe their existence to the omelette?

The egg is a leitmotif in the kitchens and studios of numerous artists, whether in sandwiches, scrambled with haddock, fried, poached or boiled. Today’s nutritionists would probably disapprove of this egg-dependency, but nobody could fault its convenience. For the artist reduced in circumstances, with no more than a gas-ring and a frying-pan, and no experience of cookery, what could be easier? The egg is nature’s fast food.

Another simple solution was the bones-and-vegetable concoction (otherwise known as pot-au-feu) adopted by Caitlin Thomas and Nina Hamnett, which could be a cheap and sustaining alternative to the omelette. In his Spartan Fulham studio the impoverished sculptor Gaudier Brzeska lived on something similar, though from his friend Horace Brodsky’s description it is astonishing that Gaudier didn’t meet his end from food poisoning several years before his untimely death in the trenches:

“I knocked, and the door was presently opened, and my nose and eyes experienced queer sensations. There was a whiff of a most nauseating smell, suggestive of stale cooking…”

The source of the stink turns out to be Brzeska’s pot-au-feu. Invited to join him for dinner, Brodsky tactfully declines. Undeterred, the sculptor tucks into the foul-smelling concoction with gusto, while cheerfully explaining his labour-saving solution to the food problem. Once a week, it appeared, he bought provisions and boiled them up in a pot together. Then all he needed to do every time he was hungry was reheat the contents. When they were finished he would start again.

“On this particular evening the strength of the odour told me that it was not freshly made. Possibly, too, Brzeska’s meat and vegetables were not of the best. Also I am sure he was not a good cook. In any case, it was not important to him. It filled his belly and kept him alive, which was all he troubled about”.

The demons that controlled Gaudier’s creativity were not concerned with the state of his digestion. Perhaps he had developed an immunity to food-poisoning. That was certainly Roy Campbell’s theory about the diet of the ex-lawyer Stewart Gray, an extraordinary character who had given away all his money and taken up squatting in empty Mayfair houses with the flotsam of models and washed-up artists of London’s pre-War Bohemia. In his autobiography Campbell propagated the myth that Stewart Gray lived on scraps from restaurants sandwiched between slices of linoleum. One would rather go hungry.

Gallery

Reviews

Julie Burchill, The Spectator

“I expected this book to be interesting, but as soon as I opened it I knew it was going to be gorgeous too, and gorgeous books which are not picture books are very few and far between. I was fair hugging myself with delight as I took in the first paragraph of the front jacket flap… this book is very much like a box of shimmering sweeties…

…Virginia Nicholson ranges over her vast smorgasbord of vivid material with all the elan of a particularly well-coordinated kitten on a keyboard. This book displays the best of Bohemia itself - playful, dazzling, original… Personally, I’m going to buy half a dozen copies for Christmas presents, and I suggest you do the same.”

•

The Observer

“This is popular history at once at its most gossipy and its most intelligent… Nicholson’s command of her sources is remarkable and she moves fluidly between her set pieces… This book is a joy because Nicholson involves herself so thoroughly in her subjects; her love of their idealism, and their earnest moral inquiry, is made extremely infectious.”

•

Andrew Lycett, The Sunday Times

“A bright, discursive social history. Nicholson succeeds in showing how unconventional ideas seeped into early twentieth-century consciousness and gradually became the norm. Her book is an entertaining, stimulating read. Well-served by excellent pictures.”

•

Alfred Hickling, The Guardian

“An outrageously enjoyable and compendious study of Bohemian lives and attitudes… Among the Bohemians is a work of social history as much as a volume of literary criticism and art appreciation…

If Nicholson had produced no more than a personal memoir of her grandmother’s eccentric cronies, the book would have been sufficient. She deserves much extra credit, however, for resuscitating many of Bohemia’s marginal figures… Her enormous cast whirls in and out of focus in an all-encompassing jig strikingly similar to Anthony Powell’s fictional recreation of the period, A Dance to the Music of Time.”

•

Miranda Seymour, Times Literary Supplement

“A racy, vivacious and warm-hearted book. Nicholson’s examination of domestic trials as the flipside of bohemian freedom is poignant and revealing… A stimulating book which offers an illuminating and well-researched portrait of life among the artists, a century ago.”

•

Christina Hardyment, The Independent

“An extraordinarily rich, provocative study. [Nicholson’s] substantial cast is stage-managed superbly…

This book is not just good fun. It raises profound questions about our lives.”

•

The New Yorker

“In a vibrant catalogue of anecdotes and tragic-comic episodes, Nicholson pays homage to British writers and artists who challenged convention before the Second World War… she casts her net wide to include the lesser-known figures…”

•

Stephen Toulmin, The Los Angeles Times

“A fascinating and purely English book, which tells us in detail about a quintessentially English society… Virginia Nicholson comes from the heart of her subject. Informative, amusing…”